Scientists Finally Understand Shark Skin, Thanks to 3D Printers

If you described a shark as a toothy torpedo covered in sandpaper, you wouldn't be too far off the mark.

It's that rough sandpapery skin that gives sharks their highly efficient swimming abilities, and scientists finally understand why.

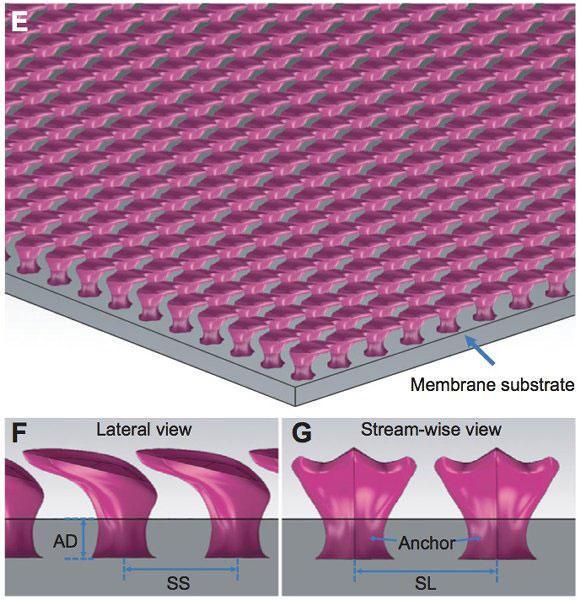

A shark's skin is covered in millions of microscopic denticles, rigid tooth-like scales that jut out from the soft skin beneath. By disrupting the flow of water over the fish's skin, it is thought, the denticles reduce drag, making for a more efficient swimmer. But to really empirically understand how the denticles do their job, you need to see how different sorts of skin coverings affect the fluid dynamics as water washes over the skin of swimming fish. You can't take a real shark and give it new skin, so Harvard University researchers Li Wen, James C. Weaver, and George V. Lauder created artificial shark skin instead. They manufactured it using a 3D printer.

At the Journal of Experimental Biology, Kathryn Knight explains:

At the Journal of Experimental Biology, Kathryn Knight explains:

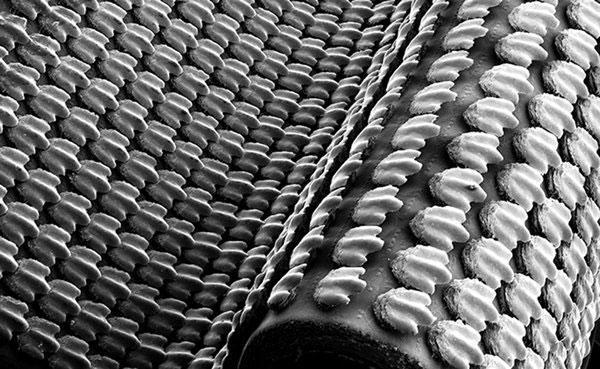

After finding a mako shark in a local fish market, Lauder took a small sample of the skin for scanning to get a high-resolution view of the surface. Next, he and Wen zoomed in on one representative denticle to build a detailed model of the structure before reproducing it thousands of times in a computer model of the skin. Then the team had to find a way to construct the model. 'After considering a number of approaches, we decided that the only way to embed hard denticles in a flexible substrate was the 3D printer', recalls Lauder, but this proved to be easier said than done. 'We had to figure out how to print themwith multiple materials... The denticles are embedded into the membrane and overlap, which posed a key challenge', recalls Lauder. However, after a year of testing different materials, printing protocols and enlarging the denticles and their spacing, Weaver finally produced a convincing sample with the denticles secured in a flexible support. 'Seeing the [scanning electron micrograph] SEM of the curved membrane with the denticles was a great moment for us', smiles Lauder, who admits that the image of the SEM in the research paper is one of his favourite research images of recent years.

Lauder's group then subjected their 3D-printed faux skin to a series of tests in water. They found that it managed to reduce drag by 8.7% when the water flowing over it moved slowly, which is consistent with the thought that denticles reduce drag. But in faster currents, the denticles actually increased drag by 15% compared to a smooth sheet. That might seem surprising at first, but sharks don't swim in a straight line, they wriggle their bodies. As soon as the researchers started wriggling their artificial skin, the swimming again become more efficient: swimming speed increased by 6.6% and the energy expended was reduced by 5.9%.

What that means is it isn't the denticles alone that account for the shark's efficient swimming. Rather, a shark relies on its rough skin combined with the wave-like motion of its body as it undulates through the water.

It's the first time that anybody has found a way to combine the two most important features of shark skin in an artificial device: rigid denticles combined with a flexible substrate. Now that they can manufacture such skin, new research opportunities have opened up to explore how the different patterns of denticles give different shark species their own unique edge.

It's the first time that anybody has found a way to combine the two most important features of shark skin in an artificial device: rigid denticles combined with a flexible substrate. Now that they can manufacture such skin, new research opportunities have opened up to explore how the different patterns of denticles give different shark species their own unique edge.

Findings from this line of research could also open up new frontiers for soft-bodied hydrodynamic robotics, and lead to innovation in the design of more efficient wetsuits and other swimming apparel.

Article first appear in Marine Wildlife Magazine

Call us and schedule your listing today! Contact Us

Copyright © 2025 Hermanus Online Magazine. Web Development by Jaydee media.