The Forgotten temples in the Karoo

Stone structures dot the veld in many locations throughout southern Africa. These were not given much thought in modern times, with landowners and archaeologists alike variously assuming that the structures were built as livestock enclosures, houses, game traps or even fortifications in the Boer War. Dr Cyril A Hromník, a Slovak historian from Cape Town, refers to ancient manuscripts as proof that the older stone walls and circles were in fact temples built by the Quena (Otentottu or Hottentots) as part of their Indian cosmological religion.

Stone structures dot the veld in many locations throughout southern Africa. These were not given much thought in modern times, with landowners and archaeologists alike variously assuming that the structures were built as livestock enclosures, houses, game traps or even fortifications in the Boer War. Dr Cyril A Hromník, a Slovak historian from Cape Town, refers to ancient manuscripts as proof that the older stone walls and circles were in fact temples built by the Quena (Otentottu or Hottentots) as part of their Indian cosmological religion.

Geelbek farm lies in the Moordenaars Karoo just north of Laingsburg in South Africa. It did not get its name

of “Yellow Mouth” from either the Yellow-billed Duck or the Yellowmouth fish, as neither of these animals occurs in this arid part of the country. The name rather refers to the presence of Quena, as the name “Geelbek” is still used to denote the descendants of these people in the northern regions of South Africa.

There are many stone structures on the farm, some straight walls and others circular in shape, as well as rock shelters with “Bushmen” paintings. For Dr Hromník these are all parts of a complex of temples that can be explained, but only if one knows ancient Indian religion and if one understands who are the Quena.

Dr Hromník has been researching the origins of the Quena and Bantu-speaking peoples for the past twenty-five years. He has come to the conclusion that the Dravidians of southern India have had an immense influence on what is now called Africa). More than 2000 years ago, the shona khanika (gold miners) from India went inland from the Mozambican coast and established gold mines in what they called Śonabar, the “Land of Gold” (MaShonaland in modern Zimbabwe) and MaKomatiland, the gold-bearing north-eastern part of South Africa (now Mpumalanga). These Indians and their Bugi labourers from Indonesia interbred with the only indigenous people at the time, the Bushmen (or Kung), and from this union sprung the Quena or Otentottu (later corrupted to Hottentoten by Dutch writers).

Dr Hromník has been researching the origins of the Quena and Bantu-speaking peoples for the past twenty-five years. He has come to the conclusion that the Dravidians of southern India have had an immense influence on what is now called Africa). More than 2000 years ago, the shona khanika (gold miners) from India went inland from the Mozambican coast and established gold mines in what they called Śonabar, the “Land of Gold” (MaShonaland in modern Zimbabwe) and MaKomatiland, the gold-bearing north-eastern part of South Africa (now Mpumalanga). These Indians and their Bugi labourers from Indonesia interbred with the only indigenous people at the time, the Bushmen (or Kung), and from this union sprung the Quena or Otentottu (later corrupted to Hottentoten by Dutch writers).

The finger dot paintings are the same as seen on the forehead of Indian women to this day.

The Quena adopted much of the ways of life of their Indian fathers. Instead of remaining exclusively hunter-gatherers like the Bushmen, the Quena lived in larger groups who panned for gold in the gold-bearing rivers and, later, also mined the gold reef and worked metals. They continued hunting wild game and gathering roots and tubers, but now they also became traders and herded the Asian fat-tailed sheep, goats and hump-shouldered cattle the Indians had brought to Africa. As they dispersed south from their origins in the region of the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, they gave names to riv- ers, mountains and other places that are still in use today. (The name Pramberg given to so many breast-shaped hills, and eloquently referred to by Afrikaans poet Boerneef, has its origin in the Dravidian word meaning female teats.)

They also retained the cosmological religion of the Tamil Dravidians, and their larger communities could afford the upkeep of a full-time priest, or suri. These suris observed the movement of the stars, especially the sun and moon, and built stone structures that aligned with prominent features in the landscape to form a huge timepiece that showed, for instance, the start of the New Year. If the sun could be seen rising at exactly the some spot on the same day of the year, as observed from an observation seat, the orderly working of the universe and the presence of their supreme and only god Śiva were once again affirmed.

It also mapped the continual contest of the male Sun chasing the female Moon, with the woman starting thin, but being a woman, appearing 45 minutes later each day and 15 degrees behind the sun until the Sun caught up with her and she became full before she disappeared to start the cycle all over again.

A couple of years ago, David Luscombe, the owner of the farm, showed Dr Hrom- ník the largest structure on Geelbek farm. It consists of two parallel stone walls that run along natural adjoining ridges, the one 530 metres long and the other 520 metres. The ends turn outward, forming a “funnel” or “chute” shape. As this was clearly not a livestock enclosure, the expla- nation was offered that it could be a game trap, with men armed with spears, bows and arrows waiting at one end while oth- ers drove game in between the walls. But, as Hromník points out, even if this was feasible, what would they do with all the meat? The Quena (and Bushmen) only took from nature what they needed and would not slaughter animals which would go to waste.

Photo Above: One of the two immense parallel stone walls 72 metres apart that form a symbolic corridor of over half a kilometre long for the Moon and the Sun and its planets

Hromník has established the cosmological relationship of these parallel walls with an observation seat and a free- standing, perpendicular wall nearby on the other side of the Geelbek River. The rantjies (ridges) on which the walls were built, he explains, align with the rising sun one lunar month before the Spring Equinox and with the setting sun one lunar month before the Autumn Equinox. The walls therefore served as a symbolic corridor for the Moon and the Sun and its planets. The precise Equinox time was obtained from the interplay between the high point of this Moon-Sun Corridor with a seat and a door in the freestanding wall to the west.

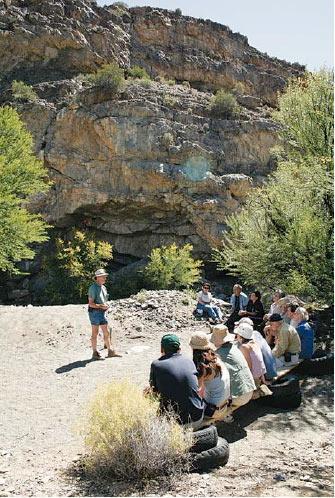

Photo Left: Dr Cyril Hromník addressing a group during one of his guided tours of the Geelbek temple sites at the time of the Summer Solstice in December. Behind him is the rock shelter identified as a Birth Temple by the red “finger dot” prints.

Photo Left: Dr Cyril Hromník addressing a group during one of his guided tours of the Geelbek temple sites at the time of the Summer Solstice in December. Behind him is the rock shelter identified as a Birth Temple by the red “finger dot” prints.

The largest extended temple on the farm forms a bow shape with three straight sides, the longest side, representing the bow, is 8,5 km long, the shorter ones representing the drawn string, each about 7,5 km.

Phillip Maasdorp showed Dr. Hromník a rectangular stone structure at the southern tip of the bow, which he spotted while riding after game. When Hromník is shown a stone structure or comes across a formation with possible religious mean- ing, he takes out his compass and looks for features in the landscape that could be used as cosmological beacons. In this case, measuring the angles connecting this structure with two prominent and named (which is rare in the Karoo) hills, Hromník recognised the shape of the bow. The conical hill at its head bore a significant name Ramkop (“Ram’s Head” or “Ram’s Hill”). Nobody on the farm could tell him how the hill had been given its name. It was there since before the first maps were drawn, up to two centuries ago. Hromník found the confirmation of the bow’s exist- ence when he located the bow’s centre and the farm, he eventually reconstructed the huge celestial Bow, and that provided the explanation for the name Ramkop: this temple complex was devoted to Rama, an incarnation of the supreme Tamil god Śiva and the greatest Bowman of all.

Hromník says it is “a masterpiece of the ancient Indo-Quena cosmological geometry. To be able to build it, the designers had to be familiar with the oldest extant holy scriptures of India. It links the Quena people of southern Africa with the oldest possible civilised ancestry anywhere on this Earth.” Hromník’s research in India and his readings of the ancient Tamil and Hindi scripts in the original languages also offered an explanation for some of the hitherto unexplained elements in Southern African rock art.

A rock shelter on the bank of the (dry) Geelbek River contains surfaces covered with “finger dots” in red and black paint. No convincing explanation has been given for these “abstract symbols” in terms of the Bushmen hunter-gatherer cultures. Hromník says the dots are the same as seen on the forehead of Indian women to this day – the “third eye” of God, also the sign of birth. The shelter is therefore a Birth Temple and a dot would have been added whenever a child was born or whenever a woman came to pray for one. A bumpy ride in a four-wheel-drive vehicle takes one to another site – and the other end of the human life cycle. The Farewell Temple consists of a hillside cave with a large pentagonal rock over the entrance, facing west and overlooking a riverbed. On the other side of the river a broad stone wall runs true south–north along the bank for a distance of some 50 metres.

The flat rocks around the cave entrance, including the pentagonal one, all bear imprints of human hands in red paint. On closer scrutiny one sees that all the imprints are of the right hand, they are fairly small and thin-fingered, and all have the pinkie (little finger) missing!

The flat rocks around the cave entrance, including the pentagonal one, all bear imprints of human hands in red paint. On closer scrutiny one sees that all the imprints are of the right hand, they are fairly small and thin-fingered, and all have the pinkie (little finger) missing!

Photo Left: A handprint on a rock face in the Farewell Temple. The missing pinkie finger indicates that the print was made by a woman whose finger was cut off according to Indian custom. Similar farewell prints are still found at cremation sites in India.

Similar handprints at other sites have been explained as possibly those of youths made during an initiation ceremony. The missing finger at this site, says Hromník, clearly establishes a link with India, where in some parts a girl’s pinkie is still cut off the moment she is promised to another family in a marriage arrangement. The Farewell Temple is where a wife came to make her last mark before she was cremated with her deceased husband (a practice still common in India today). As the cave was small and could not accommodate the large number of people who would have attended, the wall along the riverbed served as seating gallery during the ceremony.

The four quarters of the sky – or points of the compass, as they are now called - along with the movement of the sun and the moon, were key elements in the Indian cosmological religion. Some of these elements had their origin in the topography of India, but were transplanted unchanged to Africa. Heaven lay directly to the north (the high peaks of the Himalayas) and the souls who were not going to heaven, but had to wait for reincarnation, went to the south. (The Indian influence may still be detected in present-day Bantu religion, in which the forefathers reside in the south and serve as a link to the gods, who are in the north.)H

Heaven, however, cannot be approached directly by even the most worthy of souls; it can only be reached by travelling to the northeast. From the Farewell Temple, if one scrambles up next to the cave and walks precisely north-eastwards, one comes across a structure consisting of two interlinked circles – the final stopping place for the departing souls. There are two entrances: one leading north to heaven, the other south for those souls who have to await reincarnation.

Heaven, however, cannot be approached directly by even the most worthy of souls; it can only be reached by travelling to the northeast. From the Farewell Temple, if one scrambles up next to the cave and walks precisely north-eastwards, one comes across a structure consisting of two interlinked circles – the final stopping place for the departing souls. There are two entrances: one leading north to heaven, the other south for those souls who have to await reincarnation.

Photo Above: The final station for the departing souls of the cremated, exactly northeast of the Farewell Temple. The enclosure has two doors, one leading north to Heaven, the other south for souls.

Geelbek and the two adjoining farms that together belong to David Luscombe are particularly rich in stone structures. It probably served as the religious centre for a widely spread, trading and nomadic community, a place that people would return to for religious rituals. For many of the temples Towerkop (also caled Toorkop) at Ladismith, about 35 km away, serves as a reference point, as it is the most prominent topographical feature visible from the area.

Dr Hromník has been doing research on the farm for almost six years, and has mapped dozens of structures. His findings will be incorporated in a book he is now completing, which will update his research on early Indian influences in Africa. When he starts explaining things, piles of stones in the middle of nowhere assume a totally different meaning.

Source

Story & Images by Maré Mouton

Call us and schedule your listing today! Contact Us

Copyright © 2025 Hermanus Online Magazine. Web Development by Jaydee media.