Heroic HMS Birkenhead Sinks

HMS Birkenhead is one of South Africa's most famous shipwrecks. At 2 a.m. on the calm, clear night of 26 February 1852, she was wrecked on an uncharted reef off Danger Point, near Gansbaai – approximately 170 km (106 miles by road) east of Cape Town, South Africa. Tragically, there were eight lifeboats, but only three could be used. The soldiers famously stood fast, allowing the women and children to board safely. Of the Birkenhead’s approximately 643 passengers, only between 193 and 206 survived.

The troops' chivalry gave rise to the "women and children first" maritime protocol when abandoning ship, while the ‘Birkenhead Drill’ of Rudyard Kipling’s 1893 poem, Soldier an’ Sailor Too, became synonymous with supreme courage in the face of hopeless adversity. HMS Birkenhead was headed for Algoa Bay and the Buffalo River mouth with military stores, horses and troops that were to be deployed as reinforcements in Sir Harry Smith’s action against the Xhosa in the Eastern Cape’s 8th Frontier War.

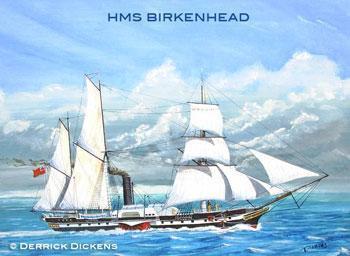

"HMS Birkenhead" by Derrick Dickens

HMS Birkenhead, also referred to as HMS Troopship Birkenhead or Steam Frigate Birkenhead was one of the first iron-hulled, combined sail and steam-powered ships, and also one of the last paddle steamers built for the Royal Navy. HMS Birkenhead was built at John Laird's shipyard at Birkenhead, near Liverpool and was initially known as the frigate, HMS Vulcan, but renamed soon after to HMS Birkenhead, after the town where she was built in Cheshire, England. As a frigate, she had two masts, and was rigged as a brig, but during her conversion to a troopship, another mast was added and she was re-rigged as a barquentine.

HMS Birkenhead was launched on 30 December 1845 by the Marchioness of Westminster and undertook her maiden voyage to Plymouth in 1846. By 1851 she had been converted to a troopship but never did service as a warship.

At 6 a.m. on 25 February 1852, the HMS Birkenhead set sail for Algoa Bay and the Buffalo River Mouth with around 643 passengers on board - under instructions to reach her destination as quickly as possible. In order to make the best speed possible, Captain Salmond hugged the South-Western Cape coastline, setting a course of no more than three miles (4.8km) from the shore. Making optimal use of her paddle wheels, she managed to maintain a steady speed of 8.5 knots.

In early January 1852, under the command of Captain Robert Salmond, RN, HMS Birkenhead sailed out of Portsmouth harbour and headed for Queenstown (now Cobh) on the West Coast of Ireland. After picking up additional troops there on 5 January, she set sail for the Cape on 7 January 1852 with troops from 10 regiments, 25 military wives and 31 children. Of these women, three died giving birth to babies during the voyage and one died of consumption.

The HMS Birkenhead arrived in Simon’s Bay (now Simonstown) on 23 February 1852 after a voyage of 47 days – 10 days longer than the return voyage she’d made from the Cape in October 1850 when she set the fastest time ever for a troopship.

After anchoring in Simon’s Bay, most of the women and children, as well as one officer and 18 sick soldiers disembarked. Over the next two days, water, coal and provisions, as well as nine cavalry horses and bales of hay were loaded for the final leg of her voyage to the Eastern Cape, where the 8th Frontier War (then referred to as the ‘8th Kaffir War’) was raging.

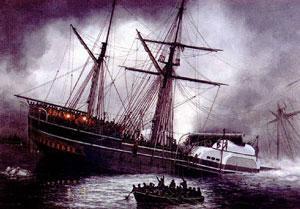

At 2 a.m. on 26 February 1852, HMS Birkenhead struck a submerged rock on an uncharted reef near Danger Point. A jagged pinnacle of rock (now know as Birkenhead Rock) tore into the bottom of the hull, instantly flooding the forward compartment of the lower troop deck and drowning more than 100 soldiers as they slept in their hammocks. Survivors of the initial impact and flooding assembled on deck - some barefoot and in their night clothes, others stark naked.

Distress rockets were fired in the hope that they would be seen, but HMS Birkenhead was too far off the usual shipping lanes. There was no lighthouse at Danger Point at the time and it was later reported that a light on shore had been mistaken for the Agulhas Lighthouse. It was also mooted that the light seen by the Birkenhead crew came from a fire set on a dune above Cape Mudge by fishermen who used it to guide their boats home. The truth may never be known.

Aware of their perilous position, Captain Salmond gave the order to abandon ship. Lt. Col. Seton, however countered his order with an instruction to “stand fast”. Several attempts were made to lower the lifeboats, but survivors later said the davits failed to function properly because of a lack of maintenance and a thick layer of paint and rust which clogged the mechanism.

After sustained efforts, two cutters and a gig were successfully launched and a small number of men and all of the women and children were later transferred to a schooner and safely reached the shore. Many tales of heroism emerged, one of which was that of teenager Ensign Alex C. Russell who was said to have given up his place in a lifeboat (and subsequently his life) for the father of one of the babies. Another was the tale of a baby who fell from its mother’s arms and drowned along with the father who was trying to rescue it. The former was disproved while the latter appeared unlikely as all the women and children were apparently accounted for.

HMS Birkenhead sank within 20 minutes after she’d struck the rock, leaving only the topmast and sails visible above the water. About 50 men were seen clinging to them, while the sea was alive with thrashing, wild-eyed horses and men desperately grasping for something with which to keep themselves afloat. Hundreds of men were drowned while scores were attacked by frenzied sharks in an area that to this day is notorious for its Great White Sharks.

BIRKENHEAD DRILL:

BIRKENHEAD DRILL:

Lt. Col. Alexander Seton of the 74th Regiment of Foot realised that if the men rushed the lifeboats they would endanger the women and children by swamping their boat, so he ordered the men to stand fast. No one moved even though the ship was breaking up around them. As a result of the failure of the remaining lifeboats to launch, around 445 of the approximately 643 passengers perished, but because of the courage of the soldiers, all the women and children survived.

The sacrifice by the troops who stood fast on deck while the women and children were lowered into one of the only three available lifeboats was an act of unparalleled selflessness and courage. It was from this wreck that the standard "Birkenhead Drill" protocol of "women and children first" was incorporated into maritime moral code.

Image: "The Wreck of theBirkenhead" (ca 1892) by Thomas M Hemy

Over the next 12 hours, a few of the soldiers swam the approximately 1.5km (0.93 miles) to shore, while others managed to stay afloat by clinging to pieces of the wreck. Tragically, most of the passengers of the Birkenhead drowned, either because they could not swim or because they succumbed to exhaustion, hypothermia or their injuries. Many got entangled in the kelp, were crushed by falling debris or were trapped in, or sucked down by the sinking ship. An unfortunate number of victims suffered the gruesome fate of being torn apart and devoured by sharks. Lt. J.F. Girardot of the 43rd Light Infantry Regiment observed that the sharks appeared to target naked people. It was speculated that this could have been because the sharks were put off by flapping clothes or else mistook the naked men for seals.

THE NEXT DAY: The Rescue Mission

By noon, the next day, several vessels, including the schooners, Lioness and Seahorse, and even a whaleboat involved in sealing on nearby Dyer Island, were frantically searching for survivors.

By noon, the next day, several vessels, including the schooners, Lioness and Seahorse, and even a whaleboat involved in sealing on nearby Dyer Island, were frantically searching for survivors.

Of the approximately 643 people aboard the Birkenhead, only 80 found places on boats. The schooner, Lioness picked up survivors aboard two of these lifeboats as well as at least 40 men that she had found clinging to the Birkenhead's main mast. In total, she managed to save 116 men, women and children. The third lifeboat managed to beach at the mouth of the Bot River, in the vicinity of Fisherhaven, near Cape Hangklip where its occupants were given food and shelter by some local fishermen before joining other survivors who had been graciously taken in by the ex-Dragoon Guard, Captain Smales of the farm, Kleine Rivier, near Stanford.

Apart from the Lioness, the schooner, Seahorse also deserves credit for rescuing 20 men who were clinging to the Birkenhead’s riggings. And not only did the whaleboat from Dyer Island help to clear away kelp that was hampering the lifeboats and rescue vessels, but it also managed to rescue four survivors. Other vessels also credited with taking part in the rescue of survivors were the Navy Flagship Castor, based at Simon’s Bay, the HMS Rhadamanthus, the schooner Megcsra and the HMS Corvette Amazon.

Apart from the survivors in the lifeboats, 68 men survived icy waters, sharks and kelp by hanging on grimly to floating bits of the Birkenhead and were eventually carried ashore by the currents. Others were found, some dead, some alive, strapped to makeshift rafts. Over the next few days the coastline was thoroughly combed for bodies which were then interred nearby in shallow graves. Surprisingly few bodies were found and buried – most of them badly mutilated by sharks.

News of the disaster only reached Cape Town on Friday, 27 February after the heroic Dr. William Culhane, Assistant Surgeon on the Birkenhead, bravely galloped through the night on a borrowed horse. It took him 20 gruelling hours on horseback to reach Simon’s Bay. The first report to be published about the disaster appeared in the South African Commercial Advertiser of 28 February 1852.

SURVIVORS AND CASUALTIES:

Sources contradict each other about the actual number of passengers that were aboard HMS Birkenhead . An initial tally of 693 was suggested when the ship left Ireland, but only 638 names were published in The Times of London after the sinking of the Birkenhead. The difference could possibly be accounted for by the women, children, sick soldiers and unknown others who disembarked at Simon’s Bay, or could simply have been the result of unreliable record-keeping.

At the time of the sinking of the Birkenhead, there appear to have been 17 ship’s officers, 125 ship’s crew, one naval surgeon, one assistant surgeon, three military surgeons, one civilian, seven women, 13 children and around 476 army officers and drafted men aboard the Birkenhead, but these numbers also vary according to the source consulted.

It is generally thought that there were between 193 and 206 survivors of the Birkenhead disaster – comprised of 113 army personnel (all ranks), 6 Royal Marines, 54 seamen (all ranks), 7 women, 13 children, 1 male civilian and unknown others. However, these numbers cannot be absolute as muster rolls, ship’s books and logs went down with Captain Salmond and the approximately 445 brave men who stood fast on the decks of the HMS Birkenhead, as she sank. The name of the man who steered the Birkenhead to her date with destiny was ironically, Thomas Coffin.

The Wreck of the Birkenhead (1901) by Charles Dixon

MILITARY REGIMENTS ON BOARD HMS BIRKENHEAD

- 2nd Regiment of Foot (Queen’s Royal West Surrey Regiment), 1 officer, 1 sergeant and 50 men;

- 6th Royal Regiment of Foot (Royal Warwickshire Regiment), 1 officers, 1 sergeant and 60 men;

- 12th Lancers (9th/12th Royal Lancers) 2 officers, 1 sergeant and 5 men;

- 12th Regiment of Foot (Suffolk Regiment) 1 officer, 1 sergeant and 68 men;

- 43rd Light Infantry (1st Battalion Oxford) 1 officer, 40 men;

- 45th Regiment of Foot (1st Battalion Nottinghamshire) 1 officer, 1 sergeant and 15 men;

- 60th Rifles, 2nd Battalion, One sergeant and 40 men;

- 73rd Regiment of Foot (2nd Battalion Royal Highland Regiment) 3 officers, 1 sergeant and 70 men;

- 74th Regiment of Foot (2nd Battalion Argyll and Sutherland Regiment) 2 officers, 1 warrant officer and 60 men;

- 91st Regiment of Foot, 1 officer, 1 sergeant and 100 men.

BIRKENHEAD HORSES:

Various sources mention that between 9 and 30 horses boarded the Birkenhead at Simon’s Bay. The conclusion drawn by diligent researchers, however, is that there were no more than nine horses on board – belonging to military officers, Wright, Bond-Shelton, Seton, Dr. Laing and Booth. They concluded that the Birkenhead was too small to safely accommodate and convey more than this number of horses along with the bales of hay needed for the voyage.

Various sources mention that between 9 and 30 horses boarded the Birkenhead at Simon’s Bay. The conclusion drawn by diligent researchers, however, is that there were no more than nine horses on board – belonging to military officers, Wright, Bond-Shelton, Seton, Dr. Laing and Booth. They concluded that the Birkenhead was too small to safely accommodate and convey more than this number of horses along with the bales of hay needed for the voyage.

When HMS Birkenhead struck the rock off Danger Point, the horses were cut free to give them a fair chance of surviving. However, it soon became apparent that the panicked horses would be a hazard as they were sliding about on the tilting deck. It was then decided to heave them overboard in the hope that they would swim to the shore. Of the nine horses, one broke its leg whilst being forced overboard and was said to have been devoured alive by sharks. The rest of the horses managed to swim to shore and local folklore has it that they, and later their offspring, roamed freely as a wild herd on the plains of the Strandveld until well into the 20th century. There is, however, documented evidence that five of the Birkenhead horses were captured and sent for safe-keeping to Mr. Mackay, Civil Commissioner of Caledon. The other three horses had ‘tales’ attached – true or otherwise.

More stories and info under "Birkenhead Horses" A resident of nearby De Kelders was said to have captured one of the horses and kept it hidden at Die Stal while he tried to find a way of removing the distinctive branding on its flank. Then there was the Baardskeerdersbos farmer named Groenewald who later boasted that his horses were the offspring of a ‘captured’ Birkenhead horse. Finally, there’s the unlikely tale that persists to this day of a Birkenhead horse that made its own way to its stable in Simon’s Bay - just two days after the Birkenhead went down!

There were happy endings to the plight of at least two of the horses – they were eventually reunited with their officer owners, Edward Wright of the 91st Regiment and Ralph Bond-Shelton of the 12th Lancers.

Two other happy endings were those of the ship’s dog (name unknown), and a couple named Mullins and their two children. The dog not only survived the sinking of the Birkenhead, but also survived being swept off the barque Eglington off the West Coast of Australia later that same year. As for the Mullins couple – Private Patrick Mullins of the 91st Regiment became separated from his wife and two children during the sinking of the Birkenhead and each presumed the other/s had drowned. Seven long years went by before Patrick and his wife were reunited by a chance encounter. The happy couple went on to produce five more children!

AFTERMATH:

Following the sinking of HMS Birkenhead, a number of sailors were court-martial. Amid great public interest, the court assembled aboard the HMS Victory at Portsmouth on 8 May 1852. As none of the senior naval officers of the Birkenhead survived, the verdict was that no one was to blame for the disaster.

Captain (later Lt. Col.) Edward W. C. Wright of the 91st Regiment told the court:

The order and regularity that prevailed on board, from the moment the ship struck till she totally disappeared, far exceeded anything that I had thought could be affected by the best discipline; and it is the more to be wondered at seeing that most of the soldiers were but a short time in the service. Everyone did as he was directed and there was not a murmur or cry amongst them until the ship made her final plunge – all received their orders and carried them out as if they were embarking instead of going to the bottom – I never saw any embarkation conducted with so little noise or confusion.

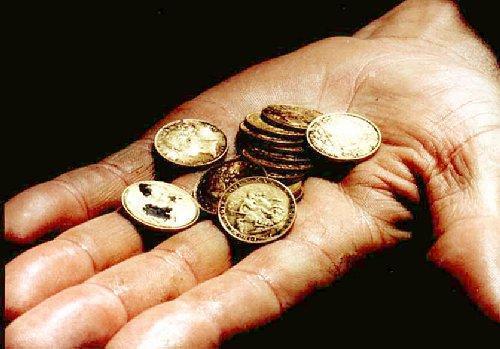

BIRKENHEAD TREASURE:

Rumours persist to this day that the Birkenhead was carrying a military payroll of at least £240,000 in gold coins, weighing about three tons, which had been secretly stashed in the powder-room before the final voyage. Numerous unsuccessful attempts have subsequently been made to salvage the gold.

Rumours persist to this day that the Birkenhead was carrying a military payroll of at least £240,000 in gold coins, weighing about three tons, which had been secretly stashed in the powder-room before the final voyage. Numerous unsuccessful attempts have subsequently been made to salvage the gold.

In 1893, the nephew of Lt. Col. Seton wrote that a certain Mr. Bandmann at the Cape obtained permission from the Cape Government to dive the wreck of the Birkenhead in search of the treasure. A June 1958 salvage attempt by a renowned Cape Town diver recovered anchors and some brass fittings, but no gold. In 1986 - 1988, a combined archaeological and salvage excavation was carried out by Aqua Exploration, Depth Recovery Unit and Pentow Marine Salvage Company. Only a few gold coins were recovered, and these appear to have been the personal possessions of the passengers and crew.

The rumour of treasure and the shallow depth of the wreck at 30m (98 ft) have resulted in the wreck being considerably disturbed over the years – and this despite it being designated as a war grave. In 1989, the British and South African governments entered into an agreement regarding the salvage of the wreck, undertaking to share any gold recovered.

Over the years suspicion has fallen on various Overberg individuals and families who have become inexplicably wealthy overnight. However, to date, the Birkenhead stubbornly refuses to give up the most lucrative and tantalising of all her secrets – her stash of gold bullion!

Source

- A.C. Addison and W.H. Matthews: A Deathless Story - The Birkenhead and its Heroes. Publisher: Hutchinson, London, Paternoster Row 1906

- David Bevan: Stand Fast – The Sinking of the Troopship Birkenhead. Publisher: Traditional Publishers, 1998, New Maldon, Surrey

- A series of articles in The Cape Odyssey

- Online websites

- Video Clip: Fasttrax Films

Call us and schedule your listing today! Contact Us

Copyright © 2025 Hermanus Online Magazine. Web Development by Jaydee media.